To protect the rights of Malagasy citizens to the land they own, in 2005 the government of Madagascar launched an innovative reform process that delegated responsibility for issuing land certificates to local districts. Land that was occupied but had not been registered with a State land title would no longer be considered the State’s property, but rather untitled private property that could be certified at the district level through local land offices.

One-third of the districts in the country now have these offices, and more than 100,000 land certificates have been issued since the reform process began. The certificate validates property rights through a process conducted with village elders and local authorities, without the involvement of a surveyor or land inspector, simply using a photograph of the district’s land to demarcate individuals’ lots.

“Land certificates carry the same legal weight as land titles,” Teyssier notes, “but cost US$15 each, a sum that is still too high, given that 92 percent of the people live on less than US$2 a day.”

The land reform process was significantly hampered by the political crisis that plagued the country for several years (from the takeover by a de facto government in March 2009 until new elections were held in late 2013) and prompted the withdrawal of the main donors from the country. However, in 2012, pilot operations in five districts were launched through a program conducted by the National Land Program (Programme National Foncier, PNF), with assistance from the French Agency for Development (Agence française de développement, AFD) and the World Bank.

The objective, Teyssier explains, was “to expand property rights to as many people as possible through a joint effort to reduce the cost of land certification, while boosting local tax revenue, by making a systematic survey of all the land lots in each village.” During the survey, each resident in the five districts had the option to buy a certificate at a cost of US$2 each. In seven months, more than 23,000 land certificates were issued, reflecting the interest in this simple and relatively inexpensive process.

Protecting investments

Bako Rabenandrasana is one of the village farmers who obtained a certificate through this pilot project. “Initially, I had some reservations,” she admits. “Although the [initial] cost is lower, once the certificate is issued, land taxes have to be paid. However, the local authorities explained that the taxes would not be too high. I ended up paying less than 1,000 ariary [US$0.43] a year for each lot, and the tax money will be used to rehabilitate our school.”

“We hope that the new government that took office recently will embrace this innovative approach, which has a successful track record in the pilot districts,” says Coralie Gevers, World Bank Country Manager in Madagascar. “The reform undertaken by the government should be expanded to ensure that the land rights of Malagasy farmers are protected by the State. Clear and transparent management of land rights is a prerequisite for political stability and economic recovery,” she adds.

A recent World Bank report titled “Securing Africa’s Land for Shared Prosperity” argued that land reform policies can boost agricultural productivity and transform the development prospects of African countries. In Madagascar’s case, the formalization of land rights will reduce disputes and encourage farmers to cultivate land and grow more food, thanks to the added security provided by the reforms.

Rabenandrasana’s certification has enabled her to obtain a loan from a microfinance institution, using the certificate as collateral. With the money, she plans to buy a few zebus and plant new rice fields.

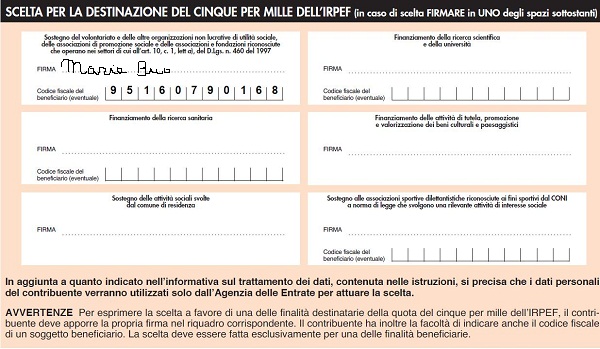

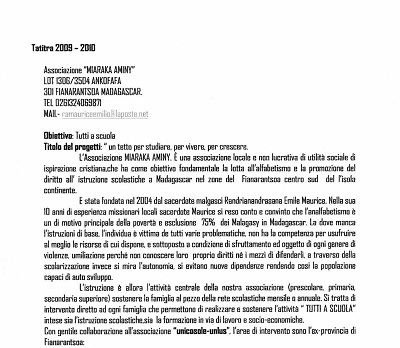

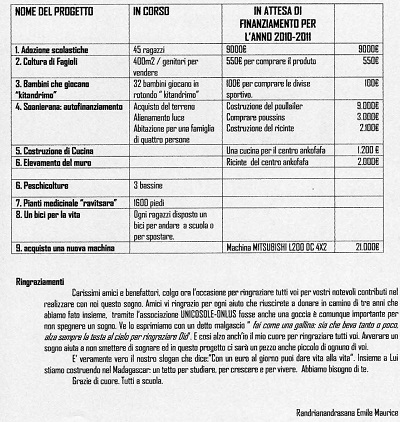

UnicoSole utilizza tutti i fondi raccolti per il finanziamento dei progetti, perchè i soci e i sostenitori offrono gratuitamenemente la loro collaborazione.

UnicoSole utilizza tutti i fondi raccolti per il finanziamento dei progetti, perchè i soci e i sostenitori offrono gratuitamenemente la loro collaborazione.